I was first introduced to disability studies through a critical literary studies class, a basic requirement for English majors where students learn different theories or “lenses” for analyzing literature. This includes theories such as deconstructionism, Marxism, Colonial and Racial studies, among several others. But I noticed that we weren’t assigned to read the last chapter of our textbook, which was about contemporary fields of study and included a small section on disability studies. Naturally, I was curious and read it. While the scant twelve pages had a lot of interesting points to ponder, I found it disappointing. The reason I was disappointed was that it failed to explain trends I have observed over the course of my life about characters with disabilities. I ended up creating my own theory to explain these trends and presented it as part of my final presentation for the class. Since then, I have been revised it countless times. Today, I’m proud to finally share it with you!

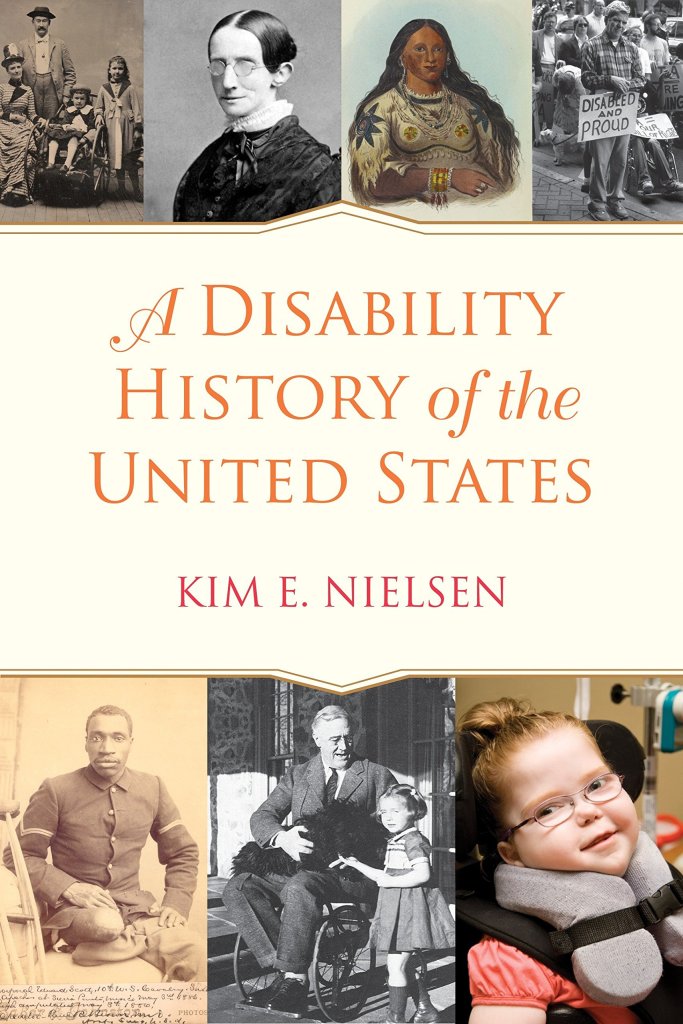

This theory is called the nullification of the disabled experience or the nullification of disabilities for short. The gist of it is to examine the relationships between power and disabilities. Because disabilities are associated with many harmful stigmas and with the lower class, disabilities and power are not presented together. Take for example the 32nd president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, whom I mentioned in a previous blog post. Roosevelt had polio and was paralyzed from the waist down, thus used a wheelchair and other mobility devices. However, he refused to be photographed with his wheelchair because of the stigmas associated with being disabled. He wanted to appear as normal as possible so people would take him seriously and not assume he was weak and feeble. He would use braces under his pants and walk with the aid of a family member to help hide his disability from the public, even though his disability was common knowledge. Roosevelt was essentially trying to “nullify” his disability in the eyes of the public to maintain power, trust, and status.

Roosevelt serves as a good example of how disabilities and power have conflict. Anyone can tell you that the appearance of power is important. The way disabilities are present in stories is equally important. Because of the conflicts between disability and power, they are often not presented as coexisting. When one appears, it often nullifies the other. This can happen in several ways. For example, if a character has a disability, then gains power—the disability becomes ignored or washed away. On the flip side of the coin, a character can be in a position of power, from which they are removed when they acquire a disability. Or another common narrative, a character seeks a cure or must otherwise overcome a disability in order to be powerful enough to defeat the big bad evil force of the story. But the simplest way a disability becomes nullified is when the limitations of a disability are ignored.

The last one is probably confusing to you. After all, isn’t part of the reason I run this blog is to help people see past the limitations of disabilities? This is true; I run this blog is to fight against the stigmas and stereotypes surrounding disabilities. But fighting against stigmas is a little different than acknowledging limitations. (Granted there is an overlap). The point here is that acknowledging and remember the limitations of a disability is a sign of respect. Ignoring limitations silences our struggles and denies that discrimination exists. But going too far to the other side by letting our limitations take center stage, will also encourage stereotypes and stigmas, which further results in overshadowing the capabilities and contributions of those with disabilities.

Think of it this way. I am a deaf person. My coworkers acknowledge the limitations of my disability by making sure they get my attention before speaking to me. They make sure to pull their face masks down so I can lipread. When I worked in a factory, my coworkers would stop machines to eliminate background noise before communicating with me. By taking these steps and accommodating my needs, they are being very respectful. It is an act of empowerment to acknowledge, accept, and respect my limits. Whereas if they don’t pull down their face masks or take steps to communicate better with me (ignoring my limitations) comes off as disrespectful.

Interestingly enough, this is the critic’s argument against the social model of disabilities. The medical model focuses only on limitations through the person’s body whereas the social model only looks at society and cultural factors. The social model doesn’t acknowledge the limitations of individuals’ bodies.

Bringing the idea of acknowledging limitations into the field of literature, I cannot tell you how many times I have seen disabled characters in TV shows or movies portrayed so accurately and amazing in the beginning, but as time goes on their limitations are ignored more and more. Which ends up nullifying the disability because the character is doing things that they shouldn’t be able to do. For example, lipreading. Lipreading is extremely inaccurate and yet, most Deaf characters I have seen on the screen can lipread every single word flawlessly. It drives me crazy! Lipreading is so much more complicated than it is presented on screen and it encourages stigma. (Check out this four-minute video that explains the complexities and issues with lipreading so much better than I ever could).

Representation like this is a slap to the face for the disabled community. Disabled individuals do not have the luxury of choosing when our limitations apply and when they don’t. By ignoring limitations when they become inconvenient, writers and directors end up nullifying the disability. It’s like saying, “We are representing a minority community—but they’re only sometimes disabled because being able-bodied is much more convenient and powerful for the story.”

I recognize this may not be the intention of the writers and directors, but it happens regardless. This is why—to be inclusive—there needs to be more people with disabilities involved in the workforce and especially in the creation of characters with disabilities. They are the ones who are going to spot inconsistencies and inaccessibilities that nullify what it is like and what it means to have a disability.

As I was writing this post, I recalled a hilarious TEDtalk given by Maysoon Zayid who has cerebral palsy: “I got 99 problems . . . palsy is just one.” In college, she participated in the theater program. When the theater announced they were going to put on a play where the leading role was a character with cerebral palsy, Zayid thought she had been born to play it. She went through the whole audition process and didn’t get the part. Instead, it went to an able-bodied peer.

Understandably upset, she met with the director to ask why. He gently explained the reason she didn’t get the part was because she couldn’t do the stunts.

“Excuse me!” she said. “If I can’t do the stunts, then neither can the character!”

This illustrates an important point in the representation of disabilities. I briefly mentioned this in a previous blog post about the representation of disabilities in Hollywood. 5% of all roles in Hollywood are for disabled characters. Of that 5%, only 2% of those roles go to disabled actors. The other 98% are played by able-bodied actors. This means that the disabled community (which comprises about 30% of the US population and well over a billion people worldwide) is being represented by .001%.

Because disabilities are often invisible and because anyone can acquire a disability at any given time, Hollywood gets away with able-bodied actors in disabled roles. Whereas other minorities—people of color, women, and those with alternative sexual orientation or gender identities—usually have visible characteristics, so Hollywood can’t get away with it as easily. Respecting, remembering, and acknowledging the limitations and the capabilities of those with disabilities is an act of empowerment. And the best way to learn about those limitations and capabilities is to learn directly from us.

So that is how disabilities can be nullified by ignoring limitations. Another way nullification happens is when a disabled person gains power, their disability will disappear—or vice versa, when a person in power gains a disability, their power disappears. Naturally, this sends several problematic messages about disabilities. A great example of this comes from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Dr. Steven Strange.* Strange starts off being in a position of power as a genius (albeit arrogant) surgeon. Later, he gets in a car crash which destroys his hands and ends his career. Strange’s life is presented as hopeless, dark, and dreary. Thus, when he became disabled he lost his power and his status—nullification of power by acquiring a disability. In pursuit of a miracle cure, Strange ends up in Nepal training in the mythic arts where he struggles a lot and blames his inability on his hands. When he does finally get the hang of magic with the use of a sling ring, from that point onward, we never see him struggling with his disability again. He appears able-bodied. So when Strange regained power, his disability seemingly disappears. That’s the nullification of disability by power gain, which results in ignoring the limits of his disability. The next time (and I believe the only time) his hands noticeably shake following his gain in power isn’t until several movies later in Avengers Endgame when Strange hands over the timestone to Thanos.

I have so much more to talk about with Dr. Strange, so look out for a blog post in the near future where I will dive deeper into everything I said above and more!

*September 2021; Writing on this character has been my most difficult blog post yet. Originally, I was planning to use this film as an example of my nullification of disability theory. In preparation, I rewatched the film and realized while this film does have moments of arguable nullification, as a whole, the film does an amazing job at acknowledging Dr. Strange’s disability. Check out my revised take on Dr. Strange here!

The message that this sends is that a person with a disability cannot hold power or be in a position of power. Furthermore, it reflects an expectation that a disabled hero cannot accomplish the same thing as an able-bodied hero.

To go further, the nullification of disability by gaining power is also common with temporary disabilities. Even an injured character—an example of a temporary disability—is often quickly healed or cured of anything that could make them less powerful or seemingly incapable of achieving their goal. For example, most science fiction and fantasy tend to have technology or magic with the ability to instantly or almost instantly heal injuries.

I think a big reason behind this is that when a writer has a character with a disability because they haven’t been taught very much about disabilities or have lacked access to the subject, they think of the disabled character as “useless.” Thus, finding a way to restore that “usefulness” quickly and reliably takes precedence.

I will admit this is something that I struggle with as a fantasy writer. Injuring characters is a great way to ramp up the stakes and build tension in a scene. For example, in one of my works I have a high-stakes chase scene with a character who ends up taking an arrow to the shoulder. Originally, I had planned for the healer on the team to instantly restore him to an able-bodied state because he has to fight in another big battle shortly after the chase. Without that instant heal option, I have to think about my story differently. How long a wound like that would take to heal naturally? I could give him a minor flesh wound (so he has time to heal naturally) or he could be fighting with his injury—which might not be such a bad idea because I can see it adding tension if done right, especially if he ends up having to sneak around the King’s patrols.

Now, I am not saying that no one should write stories with an “instant heal” or “restoration of able-bodiedness” option. If that is where your imagination takes you, I encourage you to follow it. For me, it has become a personal choice not to have instant heal as an option because I am so interested in exploring the disabled experience on the page. My intention in sharing this side of the coin is to show that there are other options. Instant heals, I feel, are something that has been done over and over. It has become something of an expectation. It’s been ingrained in stories since writing was invented and was probably around for thousands of years before that through oral storytelling. (Fun fact: the Bible is based on stories originally written in cuneiform, the oldest discovered writing system in the world which was first used around 3400 BC).

I, for one, refuse to believe that disabled characters cannot be in positions of power, nor that they cannot participate and play valuable roles in high stake plots. Writers haven’t been taught to explore the perceptions of power in regards to disabilities. Since literature embodies, reflects, and critiques culture, based on what I have seen, there seems to be a deep fear within our culture about disabilities. It is time to start exploring that fear, to question it, and to make apparent what we are really afraid of. What will happen when disabilities are allowed to linger on the page and be seen? What happens when disabled heroes are allowed to save the day?

At this point, hopefully, you are starting to see possible applications of the nullification of disability theory. If you feel that you are struggling with the concept, that’s okay. Critical literary theory usually makes more sense in application than in explanation. This post is meant to serve as an introduction. Over the coming weeks, I will be applying the nullification of disabilities theory to several different works of literature.

Don’t forget to like this post and/or leave a comment below!

FOR FURTHER READING

Goddess in the Machine – discusses a disabled character who is in a position of power and how the limitations are acknowledged

Netflix’s The Dragon Prince – nullification by ignoring limitations

The Inheritance Cycle by Christopher Paolini – nullification by overcoming a disability and power gain

James Cameron’s Avatar – is it nullification?