Genre: Children’s fantasy animation

Released September 2018 – current (the fourth season is expected to be released later this year or early in 2022)

Rated PG

Brief Summary

The world of Xadia is divided between the humans, who practice dark magic, and the elves, who use primal magic. The border between them is protected by the King of Dragons, whose only egg was destroyed years ago by the humans.

Callum and Prince Ezran find the last dragon egg and set out on a journey with elf Rayla, to return the egg to the Dragon King and restore peace to Xadia. But there are many who do not want them to succeed and do everything they can to stop them.

When I was about ten years old, I set out on a quest to find a book with a leading deaf character. I didn’t want just any random book. I specifically wanted a medieval fantasy story, with a female, deaf knight, and involved dragons. I was so determined to find this story that I got up the courage to ask the school librarian for help. We didn’t find anything available in the library, so I looked on the internet, which also had nothing. I came to realize that if I wanted to read a story about a deaf knight and dragons, I would have to write it.

Well, that all changed when I got to watch Netflix’s original series The Dragon Prince, which has General Amaya, one of the highest-ranking military official in Katolis, entrusted with guarding the human side of the Border, sister of the late Queen Sarai, Aunt to two of the show’s main protagonists Callum and Ezran, and who happens to be deaf and uses American Sign Language (ASL) to communicate.

Getting my childhood dream at the age of twenty-two, you bet I cried. While it wasn’t the first deaf character I have come across, General Amaya was the first portrayal of a deaf person in a position of power and who plays a big role across the story that I have experienced. In general, the whole show is amazing on so many levels. It was literally designed to push for diversity and representation. For that reason alone, it comes across as special and meaningful because so many minorities are being represented at once—and in positions of power! You have LGBTQ+ queens and assassins, so many powerful female leaders, and people of color by the dozen (among both elves and humans).

Not only is General Amaya deaf, but she uses real sign language—like proper grammar and everything. It’s not just a few token signs to help sell the part. And—something else that is noticeable—when she speaks, there are no subtitles to translate what she is saying. You have to know sign language to understand. I think this choice has a powerful impact because it allows the audience to see her differently. Plus there are some hilarious jokes you’ll only catch if you know sign language.

I did some more research into this. The ASL was so good, I wanted to know if there was a deaf person involved in the creation of this character. It turns out that one of the show’s co-creators, Aaron Ehasz, asked the question “What if [General Amaya] is deaf?” Ehasz also worked on another famous show Avatar: The Last Airbender, and is responsible for the tough-loving, sassy Toph, a blind earthbender. In creating General Amaya, Ehasz and the other producers reached out to several Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing organizations, met with several deaf people, and worked with several ASL interpreters to make sure Amaya’s signing was authentic.

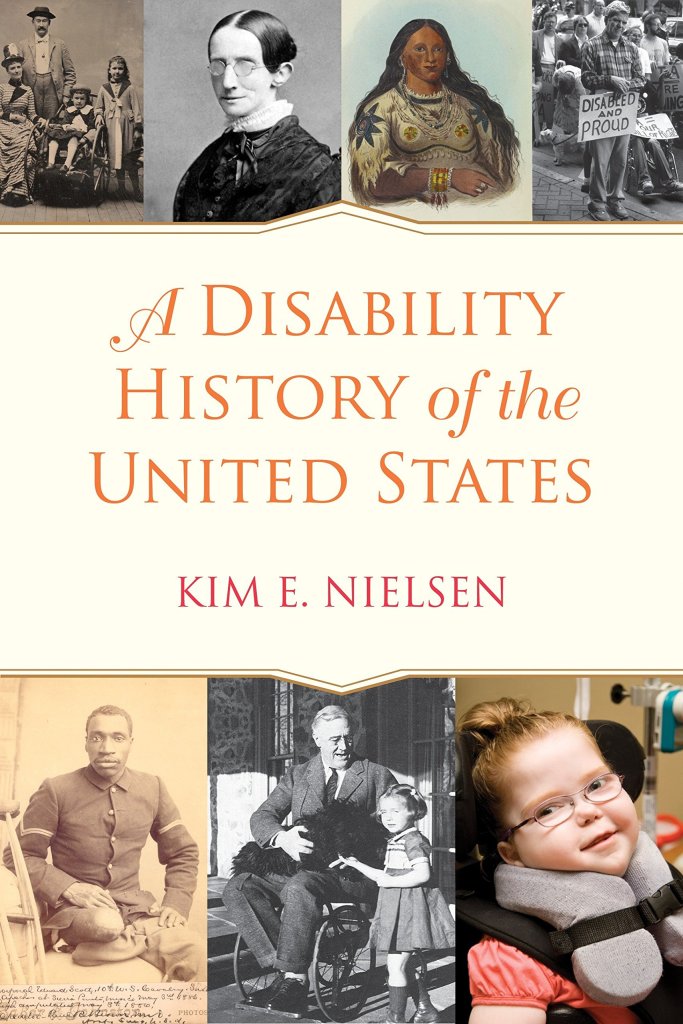

General Amaya is also in a position of power—one of the King’s most trusted advisors and one of the highest-ranking Generals in the Katolis Army. Serving in the military alone is something extremely meaningful and powerful for the Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing community. In America, disabled citizens are not allowed to join the army or serve in any related military role. Now, that might come off as strange to you and maybe you can think of a few examples of disabled veterans who are actively working in the military. That’s because the US military has a loophole. If a soldier in the military acquires a disability during active service, the military will make all accommodations necessary for them to continue doing their job. So there are people with disabilities serving, but only able-bodied people are allowed to join.

“If the US military can retain their disabled soldiers, why can’t they accept disabled citizens?”

Keith Nolan

This becomes even more questionable when looked at from a global standpoint. America is one of a small handful of countries that do not allow people with disabilities to serve, in contrast to the rest of the world where they are allowed and even encouraged to serve. Or, if you look at this issue from a historical standpoint, there have been deaf soldiers serving in every single war in US history up thru WWII.

Keith Nolan, a deaf man and a teacher at the Maryland School for the Deaf, has been fighting for years to get the military to open for the Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing. He participated in an ROTC program for two years and was able to earn the rank of a cadet private before he was barred from advancing any further simply because he was deaf. Nolan also traveled to several other countries to interview deaf soldiers actively serving in military roles and wrote a 98-page paper on why the Deaf should be allowed to serve.

“If you remember back in US history, African-Americans were told they couldn’t join the military, and now they serve. Women as well were banned, but now they’ve been allowed. The military has and is changing. Today is our time. Now it’s our turn. Hoorah!”

Keith Nolan

Nolan’s activism was successful up to the point that a bill, named after him, was drafted and sent to congress. The bill would open up a test program for the Deaf in the Air Force. If it went well, it would open the doors to regular service and test programs in other branches of the military. Unfortunately, the bill suffered from bad timing. Obama was a big supporter of Nolan, but the bill didn’t reach congress until Trump was in office. Trump has never been supportive of disability civil rights. Thus the bill ended up getting swept under the rug.

The topic of deaf in the military hits home for me. I remember the first time I was ever asked the question “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I was in kindergarten and still learning how to write. All the other kids were writing down that they wanted to be doctors, lawyers, firefighters, veterinarians, but I decided I wanted to be a soldier. I still have that assignment tucked away in one of my memory boxes.

It’s not something I talk about a lot. I used to tell people that I wanted to be a soldier, but apparently, I have such a reputation for being kind, that my friends and family laughed at the idea of me being a soldier. Growing up, it never crossed my mind that I wouldn’t be allowed because I was deaf. When I was seventeen years old, I started doing more research as I knew there were early military programs for high school students. That’s when I found out that I would never even been given a chance. That put me in a dark place for a long while. But I still hold out hope that things will change and maybe I’ll still have the chance.

To learn more about Keith Nolan’s story, you can listen to his TEDtalk, check out his website, or read more about the Keith Nolan Air Force Deaf Demonstration Act of 2018.

Coming back to The Dragon Prince, that’s one of the reasons that General Amaya is such a powerful representation. She is an example of something the Deaf community is actively fighting for. She represents hopes and dreams and inclusion and recognition.

Now, I wish I could leave this blog post at that, but if you recall my last blog post, I introduced my own literary theory about the nullification of disabilities. As much as I hate to throw General Amaya under the bus, she does fall prey to this.

General Amaya is introduced to viewers as a nonverbal character, meaning she relies on sign language for communication. So either people know sign language to communicate with her, like her nephews Callum and Ezran, or as it turns out, she has an interpreter, Commander Gren, to communicate with those who don’t know sign language. Everything is great.

That is until General Amaya assigns Gren to stay at the castle and keep an eye on Viren, while she goes on to check the border. Now, of course, deaf people do not require an interpreter at all times. There are plenty of other ways to communicate. The issue with this is that the writers didn’t show how Amaya communicated without an interpreter. Do her soldiers all know some sign language and that’s how they communicate? Is there another interpreter? General Amaya is in a powerful position where she is communicating with others all the time. By removing Gren and not showing how she communicates otherwise, it ends up nullifying her disability by refusing to acknowledge and respect the limitations of her disability.

Unfortunately, it gets worst. After she leaves Gren, she seems to gain the ability to lipread everything. There are scenes where Amaya is in a room full of people speaking verbally and she follows the conversation without any questions.

I have said it before and I’ll say it again, lipreading is extremely inaccurate! Lipreading at best—at best—can give you 30% of what someone says, depending on the language. If it is a tonal language (meaning words change based on the tone of voice, such as with Mandarin), you’ll get even less. In addition, lipreading has so many factors—how expressive someone’s face and body is, how fast they talk, if they mumble their words, and we haven’t even gotten to accents yet or being in the right mindset to lipread. Lipreading is exhausting work. I’ve had times where I am so tired at the end of the day, trying to lipread is like trying to understand a foreign language. When I reach this point, I say “I can’t understand English right now.” People laugh at that because they think I’m being funny, but really, I’m being serious. Basically what I’m saying is relying on lipreading alone is the crappiest form of communication on the face of the planet. It only works when it is put together with other things—like knowing the context of the conversation.

Yet, General Amaya doesn’t seem to have any of these issues. But wait—it gets worst (again). In Season 3, General Amaya is taken captive by Sunfire Elves. Now, the elves have a completely different set of cultures and languages than humans do. Yet, despite having no experience with elvish dialects and accents, General Amaya seems able to lipread most of what they say. Not all of it though, as they do bring in a non-native sign language interpreter into the story when they are interrogating General Amaya in a ring of fire.

To draw from my own experiences, I have a lot of opportunities to work with people who speak Spanish as a first language. In some cases, I have worked with the same people for years and let me tell you, even though I’m familiar with the Mexican accent, I struggle to lipread it. It’s like trying to lipread a foreign language. That’s why I’m saying General Amaya being able to lipread the Sunfire elves doesn’t make sense. These elves have a completely foreign accent and English is not their first language, so it doesn’t make sense that she can lipread what they are saying. In addition, she is not always at her best. In the ring of fire scene I mentioned above, she’s weak and beaten down, which would affect her ability to lipread in the first place because it takes so much mental effort to try to piece together what someone is saying even under fair conditions.

So in short, General Amaya, as awesome as she is, is a good example of nullification by refusing to acknowledge and respect the limitations of a disability. When the limits of a disability are not respected, it ends up reinforcing stereotypes. In this case, it encourages the myths that lipreading is 100% accurate and that all deaf people have an innate ability to lipread. These myths, which are already common beliefs among able-bodied people, then affect the lives of deaf people. I hate it when people just expect me to lipread what they say and refuse to listen to the accommodations that I actually need to communicate. Like when I ask for something to be written down, they refuse and point at their mouth and keep repeating what they say. In other cases, I’ve had people grab me, pull me into their face so that they speak directly into my hearing aid as if that’s going to make things clearer. It’s frustrating and uncomfortable. But it’s also frustrating because I can’t fault others for doing this as they have never been taught otherwise.

With all that said, I still love General Amaya. She is my favorite character in the series and it is so cool to see how much she is involved in the story! She’s not some token side character. She’s almost a main character at this point. I will never forget the moment that I first saw her appear on screen, the way I did a double-take when she started signing, the way the realization hit me, and the tears started flowing—this is the story I’ve been waiting for my whole life to hear, the story I’ve been looking for since I was ten. She is such an amazing character, representative of so much more than just being deaf, and her signing is authentic ASL. Her portrayal is not perfect, as I pointed out the issues with her lipreading, which leads to the nullification of the disabled experience and which directly impacts people’s perceptions and understanding of disabilities. Because like it or not, most people are introduced to disabilities through a screen, that’s why increasing accurate representation and visibility is so important to the disabled community.

The Dragon Prince is an amazing story to watch and it has so many unique elements in it. It is one that I highly recommend. And it is family-friendly too. I am excited to see the next season, which is expected to be released sometime this year or early in 2022.

What’s on your “to be watched” list? Got any recommendations for me? Comment below and let me know!