Genre: Superhero, Action, Science Fiction/Fantasy

Released: October 20, 2016

Rated: PG-13 for sci-fi violence and action

Brief Summary

Doctor Steven Strange is at the height of his career as a neurosurgeon when a car crash damages his hands. In a desperate search for a cure, Dr. Strange ends up learning magic at Kamar-Taj and comes to realize that the world is in peril.

*Disclaimer: This post will focus exclusively on Dr. Strange based on the MCU movie. I will not be covering any comics or TV shows.

Welcome back Listen Up readers! If you’ve been wondering where I have been lately, check out my last post “The Power of Voice.” This week I am excited to analyze the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Doctor Strange. Writing on this character has been my most difficult blog post yet. Originally, I was planning to use this film as an example of my nullification of disability theory. In preparation, I rewatched the film and realized while this film does have moments of arguable nullification, as a whole, the film does an amazing job at acknowledging Dr. Strange’s disability.

If you’ve been with me for a while, then you might recall mentions of Dr. Strange from previous posts. As I was going from memory, I wasn’t all that accurate. The way I remembered the story was Dr. Strange’s disability disappears after he learns to use a sling ring, thus the nullification of disability by power gain, which is to say, reinforcing the stereotype that a character can’t have a disability and be powerful at the same time. In addition to differences before and after using the sling ring, the film uses a lot of dark colors after Dr. Strange becomes disabled. After he gains power, however, colors become notably brighter and colorful. This gives the impression that life with a disability is dark and dreary.

This interpretation has several questionable messages, which I had been preparing to write on before I rewatched the film and realized I was missing a lot of points. The film is pretty consistent with portraying Dr. Strange’s disability and the color differences are more or less a reflection of his inner state rather than mirroring the rise and fall of his disability. So let’s dive into my revised take on this!

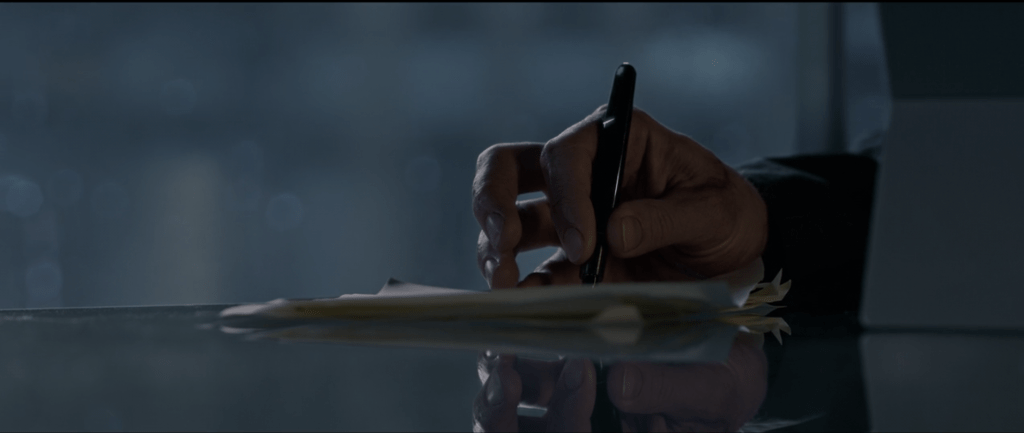

First off, I will be making some assumptions about Dr. Strange’s disability based on a couple of scenes that take place shortly after he acquired it. In one scene, Dr. Strange is seen struggling to hold a pen and print his name. In another, he attempts to shave, slowly bringing a shaking razor to his face. At the last moment, he decides against it. Based on these scenes, I’m going to assume he has issues with dexterity and grip strength.

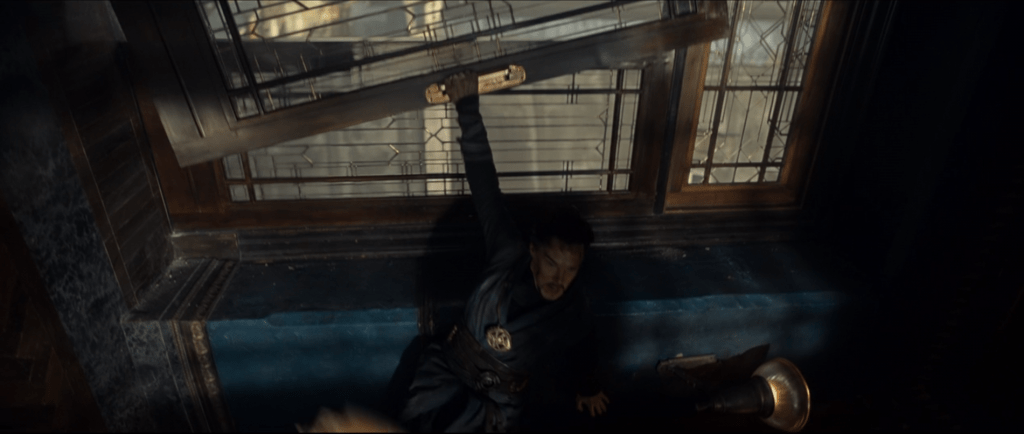

Since Doctor Strange is an action film, I paid particular attention to how he fought. Grip strength is of vital importance to throw a proper punch. The tighter a fighter can close their fist, the less prone they are to injuries. If a fighter can’t close their fist properly or if they lack the coordination to land the punch across the first two knuckles of the hand, they are at high risk of broken bones, sprains, and other types of injuries. Grip strength is also important for holding weapons. Dr. Strange, with his disability, is going to have to learn to fight without his hands and conventional weapons. The few times he does use his hands to fight, such as when trying to handle the thugs that jump him in Nepal or when he hits the door of Kamar-Taj after he is thrown out, Dr. Strange screams in pain: supporting my theory that he can’t use his hands in a fight.

Which begs the question, how does he fight?

Shortly after beginning his training, Dr. Strange learns to conquer weapons with magic. He seems to favor having magic tendrils stretched between his hands, which he uses to block blows instead of his bare hands. The tendrils can also be used offensively as a type of whip. A weapon made of magic means he doesn’t need to hold onto it, thus it can’t be knocked from his grip. It makes so much sense and I appreciate the thoughtfulness and consideration on behalf of the writers and fight coordinators. Dr. Strange’s fighting style stays pretty consistent throughout the movie, but there is some variety.

For example, in another part of the movie, Dr. Strange is training with weapons and grappling with Mordo My first reaction to this was to say that the limits of his disability were being nullified, but then I thought about it a little more. Every martial art style in the world has moves that are practiced in the studio but never used in a real fight. The difference between them is the artistic versus the practical. I’ve seen bo staff forms where people jump up and land in a split. Cool? Of course! Practical in a fight? Not so much. If someone is throwing a punch at you don’t dodge it by doing a split. However, being trained to do the splits means you can kick higher and with more control. Therefore, while there are few, if any, practical reasons to use a split in a fight, it is still important to learn the move.

Dr. Strange does train with weapons and practices grappling moves in training, but he never uses these moves in a real fight. (With one exception: when he is fighting in the astral plane, his disability doesn’t carry over and his style changes to straight grappling and brawling.) As a martial artist myself, it was cool to see how much thought and effort went into composing Dr. Strange’s fighting style. In later MCU movies, his use of magic has improved so much that he doesn’t need to fight close combat.

In hindsight, because he has to rely on magic more than any other person to be able to attack and defend himself, his disability lends itself to developing a deeper mastery of magic than his ablebodied peers. This idea is recapped in one of my favorite parts of the film when Dr. Strange is talking with the Ancient one, watching the snowfall.

[Ancient One] “When you first came to me, you asked me how I was able to heal Jonathan Pangborn. I didn’t. He channels dimensional energy directly into his own body.”

[Dr. Strange] “He uses magic to walk.”

[Ancient One] “Constantly. He had a choice, to return to his own life or to serve something greater than himself.”

[Dr. Strange] “So, I could have my hands back again? My old life?”

[Ancient One] “You could. And the world would be all the lesser for it.”

In other words, without his disability, Dr. Strange never would have reached a higher potential. Another thing I love about this conversation is that it pushes back against the cure agenda, which is an enormous ethical, political, sociological, and economic debate. The cure agenda, as it sounds, seeks to prevent, cure, or eliminate disabilities with various methods including, but not limited to: abortions of fetuses with disabilities, assisted suicide, sterilization, and social pressures to conform to ablebodiness. The cure agenda operates on the assumption that people with disabilities will always be “lesser,” and secondly, that if a disabled person had a choice, they would always choose to be ablebodied. Of course, the cure agenda is downright offensive to me and many other members of the disabled community. It is, sadly, a modern matter of life and death. You can read more about the harm a cure agenda can lead to in this blog post: “Disability History, Part 3: Aktion T4 and the Holocaust.”

The last aspect of the film I will cover today is Master Hamir, who is another character with a disability. Viewers might remember that he was introduced near the beginning of the film when Dr. Strange mistakes him for being the Ancient One, but his disability isn’t revealed until later. When Dr. Strange stubbornly blames his inabilities to do magic on his disability, the Ancient One asks Master Hamir to provide a demonstration to show that hands are not a requirement to perform magic. But here is what upsets me: when Master Hamir pulls back his sleeve to reveal his missing hand, it’s presented in a way that’s meant to shock the audience. The camera focuses only on his scars and missing hand. This emphasis essentially says that his disability is the defining feature of the character.

To go into this a bit deeper, people with disabilities face an ongoing struggle to get acknowledgment past their disabilities. Now, make no mistake, many of us are proud to be disabled. It is a part of our identity and it shapes how we see the world. But we are more than our disabilities.

To explain this idea better, I’ll share a story from my own life. Back in the summer of 2018, I was job hunting. As a deaf/disabled person, there are extra barriers in my way to getting a job interview. Many companies conduct a phone interview before conducting an in-person interview. This was the case with my local grocery store. They called me and started asking me a lot of questions. Of course, I had to ask multiple times for things to be repeated. “Sorry, I have a hard time hearing on the phone,” I would say, “Would you repeat that please?” Eventually, the caller said, “Yeah, this isn’t going to work out,” and hung up on me. After that, I was invited to an interview at a local bread baking company. I was lead through the kitchen to an office in the back. Along the way. I noticed the radio was blasting above the noise of the machinery and chatter of the workers. I did the interview and was offered a job on the spot. I politely declined because the noise level meant I wouldn’t be able to communicate effectively.

Yet another employer invited me to a group interview. Since I am not comfortable talking about personal accommodations for my disability in a group setting, I asked for a one-on-one interview. I didn’t receive a reply until two months after the initial interview, by which time I had found other employment.

Then one day, I received a call from Joanns asking me to come in for an interview. It was the second interview I’ve had in months and I was excited at the idea of working in an art supply store. I was particularly excited about the employee discount on fabric!

It was one of the best interviews I’ve ever had. I was chatting and laughing with the interviewer. She asked about my art projects and I showed her pictures of my quilt projects and paintings.

“Rachel, I am very impressed with you,” she said with a smile, “I think you’d be a perfect fit for this job. Do you have any more questions for me?”

I smiled, knowing that I nailed the interview. But now was the scary part. Bringing up my disability. Because there are so many stereotypes associated with being disabled, I wait to discuss it until the employer has a chance to get to know me a little and after we discuss my qualifications. I have found this technique usually works quite well for me. Usually.

“Actually, I do have something else I’d like to discuss.” I said. “I have a disability.”

She raised her eyebrows in surprise.

“I’m deaf.” I pulled back my hair, turned my head, and pointed to my red hearing aids. “So that means that sometimes I have a hard time understanding what other people say.”

When I turn back to her, her smile is gone. Her eyes racked me up and down like I had told her I was some kind of alien from outer space. I had a sinking feeling in my stomach. At this point, most employers start asking questions about my disability to better understand it and my needs. Instead, she sat in silence.

“You don’t look deaf.” she finally said.

I was flabbergasted. What was I supposed to say to that? What do people think a deaf person “looks” like? Trying to save the sinking ship, I asked if she had any questions or concerns about my deafness.

“No.” she stood up from the table and walked toward the door. I realized the interview was over.

“Um,” I stood up to follow her, still trying to salvage the interview. “If I get the job, when should I expect a call?”

She walked me to the front of the store. “We’ll call you.” She refused to look me in the eyes, holding the door open. It wasn’t enough for her to walk me out of the interview, she had to walk me out of the store.

Refusing to show weakness in front of her, I thanked her for the interview and got inside of my car. And then I cried. Big heaving sobs that made me so dizzy I thought I might pass out. I had no idea what I was supposed to do in this situation. I wasn’t even sure if it was illegal for her to walk me out of an interview for being deaf (it was). I didn’t have any money for an attorney, I was a college student for crying out loud. What’s more, even if I did take the matter to court and I was hired, I had no interest in working with the company anymore. But the worst part of it all? Living the fear that I always had as a child, of being denied job opportunities and more because of my disability. That’s what hurt the most. It was a nightmare that became real.

Sometimes it does not matter how talented you are, how many skills you have, how many qualifications, or how much experience you have—when you have a disability, that is the only thing some people will choose to see.

That’s why I was disappointed by how Master Hamir is portrayed only for his disability. He’s an image, not a person. I know exactly what that feels like and it is not a good feeling. It’s being invisible in all but one aspect.

Obviously, I have made some personal connections with Master Hamir and maybe that’s all it is. But I feel strongly that if Master Hamir had a few lines to speak or if he had been shown in the background fighting or teaching others, if there was more to his image than just his disability, I’d probably see him in a different light. As it stands, the way his disability was presented is disappointing.

To end on a positive note, one of the things I loved about the film is all these little, inmate moments and scenes where Dr. Strange is learning to adapt to his disability. He holds a cup of tea with two hands to keep it steady. After he learns to use an electric razor, he starts wearing brighter clothes, showing that he’s growing into his disability. And I love the closing scene where Dr. Strange holds his broken wristwatch in his hands. And in future movies, he frequently wears gloves which can be a form of assistive technology for his hands.

In relation to the scenes I originally interpreted as being nullified because Dr. Strange’s disability seems to disappear, I’ve realized I have overlooked a factor. Not all disabilities are constant. His hands could be steadier one day, but not the next. These scenes might not be reflecting a disappearance of his disability, but rather the inconsistency of it. I have included a few photos below of particular scenes that made me question whether or not his disability was being nullified. Comment below and let me know what you think of these scenes!

Dr. Strange’s next appearance in the MCU will be in Spiderman: No Way Home on December 17, 2021. If you haven’t seen the official trailer for it, here is the video link. He will also be getting a second movie Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness on March 25, 2022, which is rumored to be the next biggest film in the MCU because it will change everything we think we know.

Thank you all for reading today’s post and especially thank you to my readers who have been reaching out to check up on me and for encouraging me to keep writing.

Thank you for your patience as I have not been able to post as previously scheduled. I am still struggling with my mental health, but I am working on building better strategies to manage it. However, I am not sure what my posting schedule will be for the next while. The good news is that I am still working on writing and will be covering some exhilarating topics in the near future! Make sure to sign up for email notifications at the bottom of Listen Up’s home page or follow Listen Up’s Facebook page to stay updated on the latest posts.